Iframes… Can’t live with them, can’t live without them. Is it just me or anyone else is also wondering why these guys are still being used even though the 90s are long gone? Well, believe it or not - no one has come up with a better alternative for embedding another HTML document into your page since Microsoft first introduced the <iframe> tag in 1997. Not until recently, at least.

Web Components vs Iframes

Need for a change

If I were to associate each HTML tag with a person (and I should definitely copyright this idea), iframe would end up being an old great-grandma who has been around since the last century and persistently does a decent job of forgetting your name and falling asleep at random times, so everybody kind of got used to it. And yes, this tag was allowed into HTML5 so it will live on for another decade at least. No inheritance for you anytime soon, pal.

Of course, I used iframes numerous times in my work but have never been comfortable with the idea. When my perfect_page.html embedded - via an iframe - another HTML page, I couldn’t help the feeling there was an Alien living inside my document. With its own <head> and <body>! Ready to burst out and rip my precious page apart!

So when I faced a challenge that would normally require me to use an iframe, I was very reluctant. Hasn’t anyone come up with a better idea YET, seriously? Vehicles have landed on Mars and I have an AI woman living in my cellphone, yet still we have to use iframes to embed an external HTML page? No way. I started doing some research and - hallelujah! - stumbled upon the Web Components. Never heard of it? Google it. Seriously, Google it because it was them who initially proposed the concept of encapsulating reusable components and they rarely go wrong.

There are 4 cornerstones to the Web Components, but there’s one I’ve been particularly interested in - HTML Imports. The idea is that you use the good old <link> tag to add a reference to the page you want to embed, like this:

<link rel=“import” href=“<path to the HTML page>”>That simple?! Well, almost. We’ll discuss technical details a bit later. First off, I’ll briefly talk about the challenge that I was tasked with.

Visual implementation

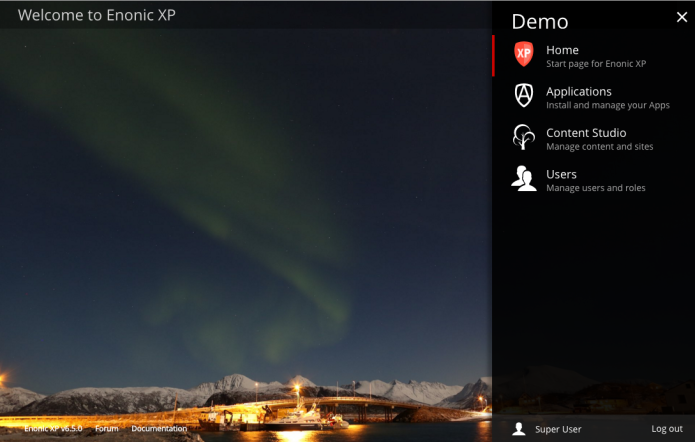

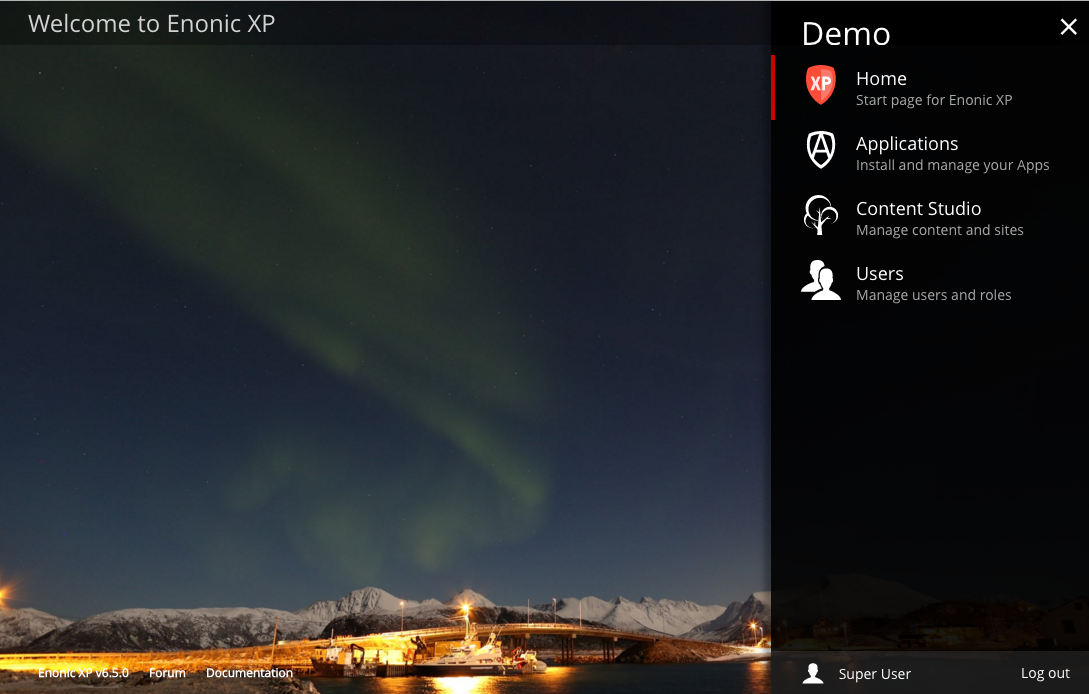

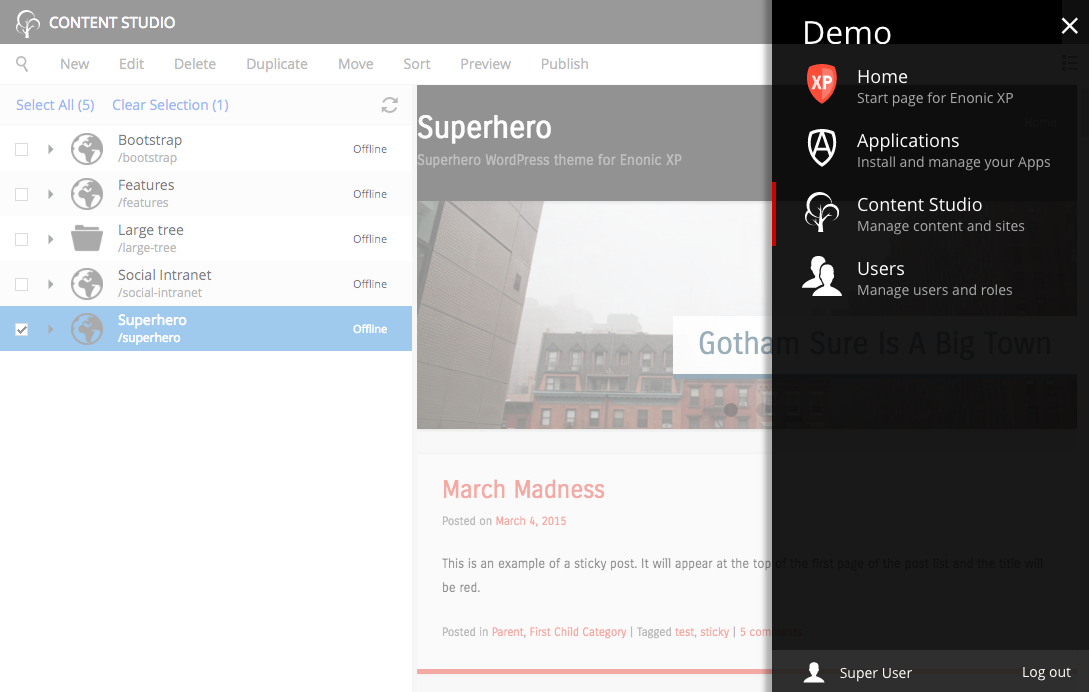

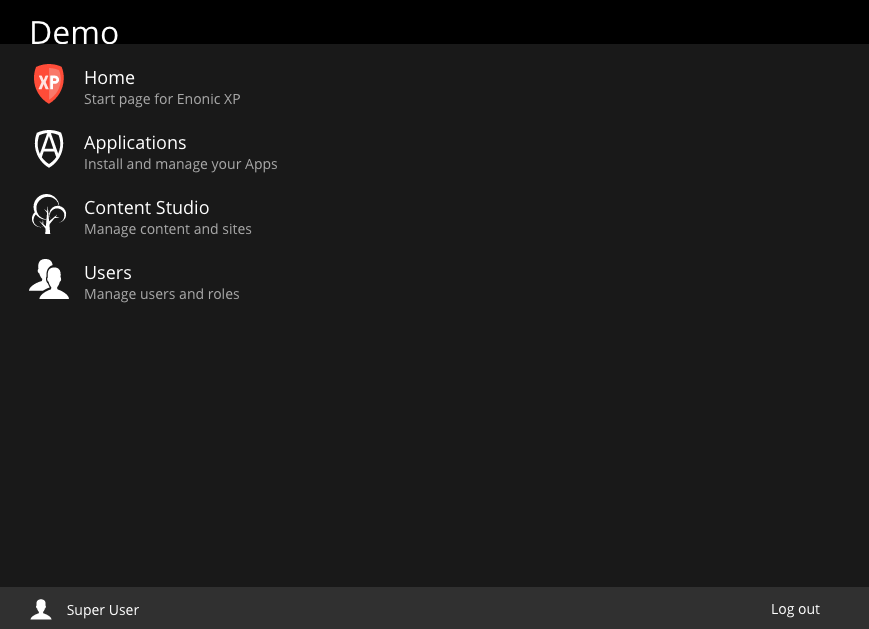

Administration module of Enonic XP can host unlimited number of fullscreen applications - internal (created by us here at Enonic) and external (made by customers or members of our community). So what we needed was some kind of a launcher, basically a window or a panel that would list all available apps so that user could quickly switch between them. Not only that, but it also should have been extremely simple to embed this launcher by simply adding a reference to the application’s entry point.

I’ll leave out the intriguing details of building the launcher panel itself, but that’s how it ended up looking when expanded inside the main admin dashboard:

…and when expanded from inside of our Content Studio:

Pretty fancy, huh? Almost as beautiful as Picasso’s work except here you don’t have to pretend that you like it to look smart.

See the panel titled “Demo” on the right-hand side? Well, this is actually a separate HTML page. This is how it looks when opened directly in the browser:

As you can see, the page itself is taking up the entire available height and width when opened directly, but when embedded inside an app it’s constrained by the container div with fixed width which makes it look like a panel. Imagine it could be anything inside that panel, really - a weather widget, Google Analytics for your site, stock quotes, pictures of cute unicorns - it’s all down to your imagination (but remember - your boss is probably looking over your shoulder, so be careful).

When the “X” icon is clicked, the panel collapses via some smooth animation into a “burger” icon which is always rendered in the top right corner to give user quick access to the panel and the applications inside:

So, to sum it up - the hosting application has no idea about what’s going on in the launcher panel. The only thing it should do to embed the panel is add a reference to the launcher.js file that does the job of creating the constraining div and embedding the launcher’s HTML page inside that div.

Well, actually the hosting page should add one more reference if you want your HTML Imports to work in all modern browsers. At the moment of writing, it’s only Chrome and Opera that natively support Web Components in their entirety. Other major browsers either partially support them or claim they don’t plan to support them at all (those guys probably still think the Earth is flat). So, if you don’t want Firefox/Edge users to see a blank space where your embedded page is supposed to be, you need to download and include in your page something called Polyfills. They will make sure that Web Components are working seamlessly in your solution. You can find installation guides on the Web.

Getting it to work

Now, let’s see how the embedding process works.

Let’s imagine this is the HTML page to be embedded:

..and this is the main HTML file of your application that is going to host the page above:

The first reference inside the <script> tag is the Polyfills library I talked about before. (Never mind the weird stuff in curly brackets - this is Moustache formatting that will be dynamically replaced with absolute path in our solution.) The second one is the JavaScript file that does the dirty job of embedding the external page. Let’s look at how it does that.

This little guy is like a bottle opener - looks simple but gives you indefinite possibilities. In our solution it obviously does more stuff besides what’s shown here (panel animation, keyboard navigation etc.) but you don’t need anything else in order to embed an external page, really.

The first function creates a <div> that will be a container for the page being embedded. The second function, createLauncherLink, is where the magic happens.

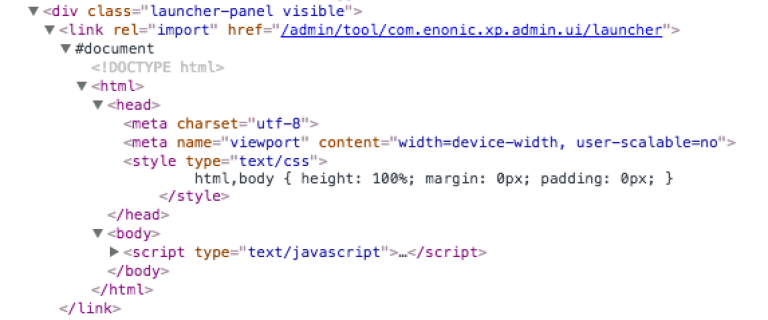

First, it creates a <link> element which then gets added to the <div> container described above. It ends up looking like this in your page’s DOM:

It works! Between the <link></link> tags, inside the weird #document container (which is in fact Shadow DOM, but don't get scared just yet), I can see contents of the HTML page I targeted with the href attribute of the <link> element.

I hate big but’s and I cannot lie

There’s always a big “but”, right? I remember the first time I popped my Web Components cherry by embedding a simple HTML page consisting of a single <div> - I was so happy to finally see it sitting inside my host page’s HTML but… I couldn’t see the damn div on the page!

Well, that’s the thing with HTML Imports - by default, it would simply place the page contents inside the so called “Shadow DOM” (which is the #document container we saw above) to make sure it's encapsulated from the host page. If your source page consists purely of JavaScript code then you’re good to go, it will run on the host page. But if it includes some visual elements then you will have to add them using some JavaScript magic. One might argue it’s actually a good thing - unlike with iframes it’s totally up to you to decide what parts of the embedded page you want to add to your host page.

Let’s look at the second half of the createLauncherLink method:

link.onload = function () {

container.appendChild(link.import.querySelector('.launcher-main-container'));

};We cannot access embedded page’s DOM document until the link element fires its “load” event, hence we need the “onload” event handler. Once we know that the page is loaded (or - in other words - once it’s landed inside our host page’s Shadow DOM), we can access its own DOM document by reading import property of the link element.

One more time - link.import IS your embedded page’s DOM document. You can call, for example, link.import.querySelector() method to find any visual element on the embedded page and add it anywhere to your host page. Which is exactly what we do here - we fetch the main div of the embedded page and append it to the constraining div of the host page.

And that’s how it looks with the visual part injected:

Look at how the launcher-main-container div is neatly placed along with the <link> element inside the launcher-panel div, as if they have originally been a part of the host page.

Recap

Ok, let’s quickly run through the whole thing again. Say, you have two pages, parent.html and child.html and you want to embed (entirely or partially) the latter inside the former.

- Make sure Polyfills are downloaded and referenced from parent.html

- Add a link element to the parent.html, looking like this:

<link rel=“import” href=“child.html”> - Should you embed visual elements of child.html, add “onload” attribute to the

linkelement where you specify a JavaScript handler function:<link rel=“import” href=“child.html” onload=“onImportReady()”> - Create the handler function that finds element(s) in the embedded DOM document (via

link.import) and appends them to the host DOM document.

Pros:

- Lightweight. You no longer have the entire HTML page sitting inside your document.

- Full control. It’s up to you to decide what parts of the external page you want to embed.

- Encapsulation. Stylesheets and scripts inside the embedded page are isolated inside the Shadow DOM of your host page. However, you can still access the main document from inside JavaScript of the included page.

- You sound cool when saying “I implemented Web Components in our solution. Iframes are so 90s…”

Cons:

- You need Polyfills library for cross-browser support

- You need to know a bit of JavaScript if you want to embed selected elements from the page

Yep, that’s pretty much it. Now go and kill your darling iframes.